There’s a reason we call the Capital Dilli dilwalon ki. It accepts people from all over the world with open arms. The sentiment is shared by those who have sought refuge here, and have made it a home away from home. The city, its lanes, and its ways have a strong hold on the lives of these refugees.

“Yes, there is pain. Yes, there are scars... but Delhi has given us a chance to rebuild our lives,” says a grateful Shabber Kyamin, a Rohingya from Myanmar.

As more and more people from different lands settled here, Delhi, too, was introduced to their cultures, and some of its areas became synonymous with them — Majnu Ka Tila with Tibetans, Old Delhi with Afghanis, and Jamia Nagar with Rohingyas. So clearly, Dilli hai sabki!

‘It feels like home’

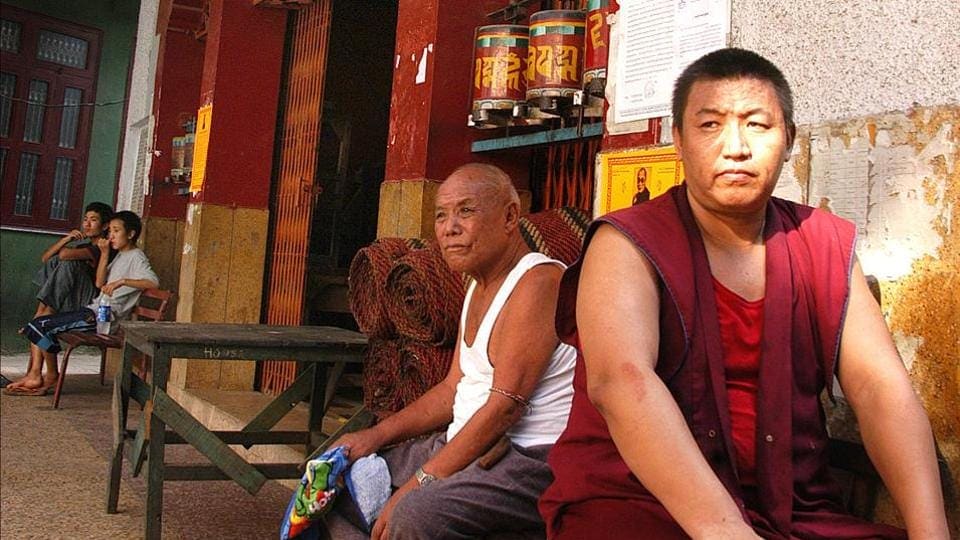

Majnu Ka Tila that houses the Tibetan community is more like Little Tibet in the heart of the Capital. Thousands of refugees have settled down here, running their businesses successfully, gaining popularity for their culture — from fashion to food. “My parents shifted from Tibet to Delhi... perhaps in 1962. They tell me several stories of how people left Tibet in hordes... when they came down here, they started a small eatery and now it’s one of the most popular restaurants in the area,” says Sanya Wangdue (name changed), who also owns a guest house in the area. “This is like our own country now. We’ve never faced any discrimination or hostility. I don’t know if it would’ve been possible for us to start life anew in any other country,” says Sanya.

The Warrior from Afghanistan

In the bylanes of Khirki Extension, amid rubble, we find Sydeqa. She fled Afghanistan amidst attacks on her life. She is trained in combat and weapon handling, and perhaps the tools she acquired as a warrior allow her to combat with the struggles of her new life. She is hoping to get refugee status in a few months. “I am thankful to

this country for providing me home and safety. I live with my husband and a new born baby,” she says, adding that she does miss the little things but realises they came at a cost. “Vahan Eid saat din tak manayi jaati thi, yahan bas teen din ki hoti hai,” but due to targeted attacks, common people lived under threat. “Kabhi barood gir jata tha...” The 35-year-old is relieved that her baby is far away from the war-torn environment, but she wishes for a stable income. “Yahan Afghanon ke liye kaam nahin hai. My husband earns on a daily basis and that, too, if he

finds work,” she says.

However, Nooran Qasim, who came to India in 2009, works at an Afghani restaurant in Old Delhi, and loves the

city and the “somewhat successful” career. “I love to be here everyday when I wake up. Dilli sabki hai... yahan bahut communities hai, toh acceptance high hai.”

The activist from Congo

Then there is Patrick. He tells us that he lives in Nehru Place. He was a human rights activist back home in the Democratic Republic of Congo, thrown into jail for his activism. When he came out, papers to go to India were shoved into his hands and now he’s here. It has barely been two weeks since the UN awarded him refugee status after four years of living in Delhi. “India saved my life and I am grateful for it. It is my refuge and I am looking for a better future here,” says Patrick, a native French speaker having to learn English and the bare bones of Hindi. He works as a hairdresser, “but only by appointments,” and also plays in a band.

His struggle lies in having left behind a family, scattered across the world. He has no idea where they are.

When not all hope is lost

“No one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear saying — leave, run away from me now, I don’t know what I’ve become, but I know that anywhere is safer than here,” says Shabber Kyamin, a Rohingya from Myanmar, who left his place of birth in 2005, shares the last verse of a Warsan Shire poem describing what he went through.

“The conditions were deadly there. What one could see is genocide, ethnic cleansing and politically targeted groups. We had no option [but to leave]. I came alone, but now I’m married and have two kids. I run a mobile accessory shop and have my own small business in Rajasthan... All I can say is that I’m thankful to this country, this city.”

Shabber got the refugee status a few years back. “In Delhi, more than 800 Rohingyas got the refugee status.”

He also works with Rohingya Women Rights Initiative. “We are trying to uplift the our community in terms of health, education and shelters,” adds Shabber.

Follow @htTweets for more