(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump's new budget proposal makes some heady economic projections -- 3% annual real economic growth for the first half of the decade -- to justify his policies and make the budget deficit look smaller than it might otherwise be. That's a lot higher than mainstream economists at the Federal Reserve and Congressional Budget Office believe is likely based on productivity gains, an aging population and slower growth in the labor force. But Fed and CBO forecasts often are wrong, and during much of the past decade economists and policy makers have misjudged the extent of slack in the U.S. labor market. An aspirational economic growth projection, even if it may not be realistic, is a good reminder that we shouldn't underestimate how much economic growth is possible in the U.S.

In contrast to the Trump administration's forecast, the Fed and CBO are projecting growth of little less than 2%. Their reasoning is straightforward -- productivity growth since the Great Recession has slowed, averaging about 1% a year during the past decade. Forecasters also point to slower growth in the labor force, which tends to put a damper on economic growth.

But the same kind of analysis three years ago at the outset of the Trump administration lowballed the economic growth that followed. The Fed's economic projections for 2017 through 2019 made at the end of 2016 estimated that real gross domestic product growth would come in at 2.1%, 2.0% and 1.9%, respectively. CBO forecasts made in early 2017 were similar. What we actually got was 2.8% real GDP growth in 2017, 2.5% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019. That adds up to an economy that's $300 billion bigger today than predicted three years ago, and it's coincided with lower unemployment, inflation and interest rates.

It's true that part of that higher-than-expected growth can be traced to the fiscal stimulus from Trump's tax cuts, but that increased growth also has come without faster inflation or higher long-term interest rates. This suggests that fears of bigger budget deficits crowding out private borrowing were misplaced. If the fiscal costs of the tax cuts were low, it stands to reason that another round of fiscal stimulus -- perhaps focused on infrastructure spending or benefiting workers more directly -- also could boost growth with little or no additional inflation.

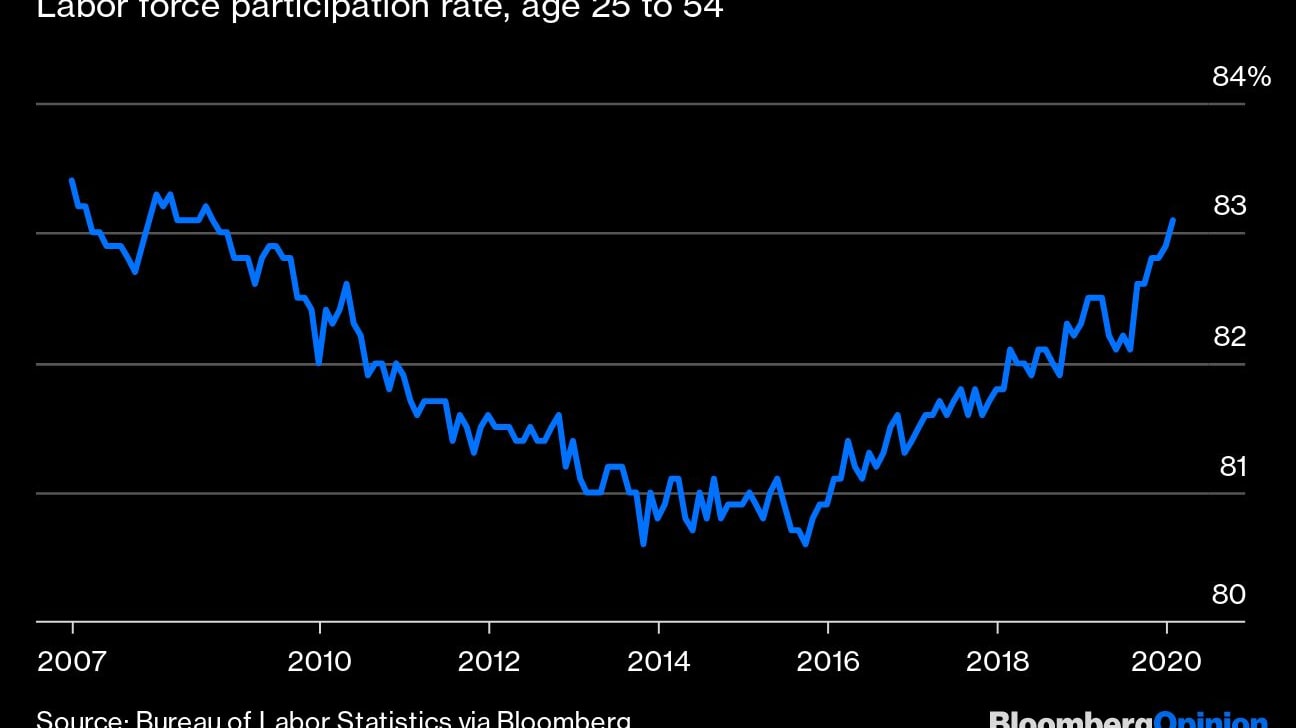

The reason inflation has stayed in check is because of an uptick both in productivity growth and labor force participation. Neither is back to levels seen in the late 1990s, but during the past three years productivity growth has ticked up to an average of 1.4%. And the labor force participation rate, particularly for prime-age workers, has defied demographics and picked up after initially declining in the years after the financial crisis. The participation rate for workers between the ages of 25 and 54 has increased 1.6 percentage points during the past three years -- the fastest three-year growth rate since 1990 -- to the highest level since mid-2008:

Although there are surely limits to productivity and labor force growth, we shouldn't assume we know what they are. Labor force participation rates are higher in many other countries than they are in the U.S., and productivity growth has been higher in the past than in recent years. Fixed investment in the U.S., whether in the public or private sector, has been sluggish for the past decade. It stands to reason that labor force participation and productivity growth in the years ahead could increase still more with a better mix of federal economic policies.

What's important to keep in mind is that forecasts from mainstream economists have an indirect impact on policy. Fed and CBO economic projections during President Barack Obama's administration were too rosy and assumed that inflation would start rising at much higher levels of unemployment. The result was less aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus than the economy needed, something that's only obvious now in hindsight. Congressional Republicans also were an obstacle to the fiscal stimulus the economy needed during those years. Their efforts also played in role in leading the Fed to adopt monetary policy than was too tight while also browbeating Democrats into not pushing for more pro-growth policies.

Trump's 3% growth utopia may be too optimistic, but there's good reason to believe the Fed and CBO forecasts of sub-2% growth are too pessimistic. Faster growth like that of the past few years is possible, and it's good that we have a White House willing to push for it.

To contact the author of this story: Conor Sen at csen9@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com/opinion

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.