Megabanks at Home, Minnows Abroad

(Bloomberg) -- Time and again since Japan emerged as a global economic force, its financial leaders have hatched plans to translate their influence into investment-banking clout. Time and again, they’ve failed.

The retreat sounded by Nomura Holdings Inc. last month marks just the latest Japanese overseas flop, prompting current and former executives, as well as analysts, to question if they can ever make it in international capital markets.

“Japan is a manufacturing powerhouse but a financial lightweight,” says David Threadgold, a Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analyst in Tokyo who has followed banks there for more than three decades.

Their weakness overseas is an urgent handicap for Japan’s biggest banks, which are facing tough times at home. Results last week highlighted the effect of a weakening economy and rising trade tensions, with Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group Inc., Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. and Mizuho Financial Group Inc. all posting net income projections that missed analysts’ estimates. Those, combined with entrenched rock-bottom interest rates, point to cost-cutting as a top priority—especially abroad.

But since Nomura brought in top bond traders to sell U.S. Treasuries to domestic investors in the early 1980s, Japanese banks have stumbled on practices that work at home but not so much on Wall Street and Canary Wharf: excessive risk aversion, centralized control that values process over profit and, most critically, personnel policy that rotates senior executives every few years.

“Decision-making in every Japanese company is consensus-based, process-heavy and very slow,” says Threadgold. “It’s easier to get cultural buy-in for that style from auto workers in Tennessee but very difficult to do so from investment bankers in Manhattan or London.”

The latest faux-pas are especially stark because Japanese banks had the chance to hit their U.S. and European rivals when they were bloodied from the financial crash of 2008. The story is best seen in the diverging strategies and outcomes at Nomura, the largest secutiries firm, and the No. 1 bank, MUFG. With this month’s 15 percent plunge, Nomura’s shares have lost 81 percent since the start of 2008; MUFG has lost 52 percent. Both lagged the benchmark Topix Index.

MUFG put $9 billion into Morgan Stanley at the height of the 2008 crisis and is now the biggest shareholder of the U.S. investment bank, cashing in the dividends from the much more profitable business.

In contrast, Nomura bought the European and Asian businesses from bankrupt Lehman Brothers. The combined capital markets revenue of the acquired business and Nomura was $12 billion in 2007. Today’s it’s around $5 billion. With too many employees and too few clients, the Japanese firm is again on the defensive: it’s slicing $1 billion of costs and eliminating about 150 jobs across the Americas and Europe, the Middle East and Africa on top of reductions in Hong Kong and Singapore. It was the fourth time in four decades: Nomura had attempted global prominence in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

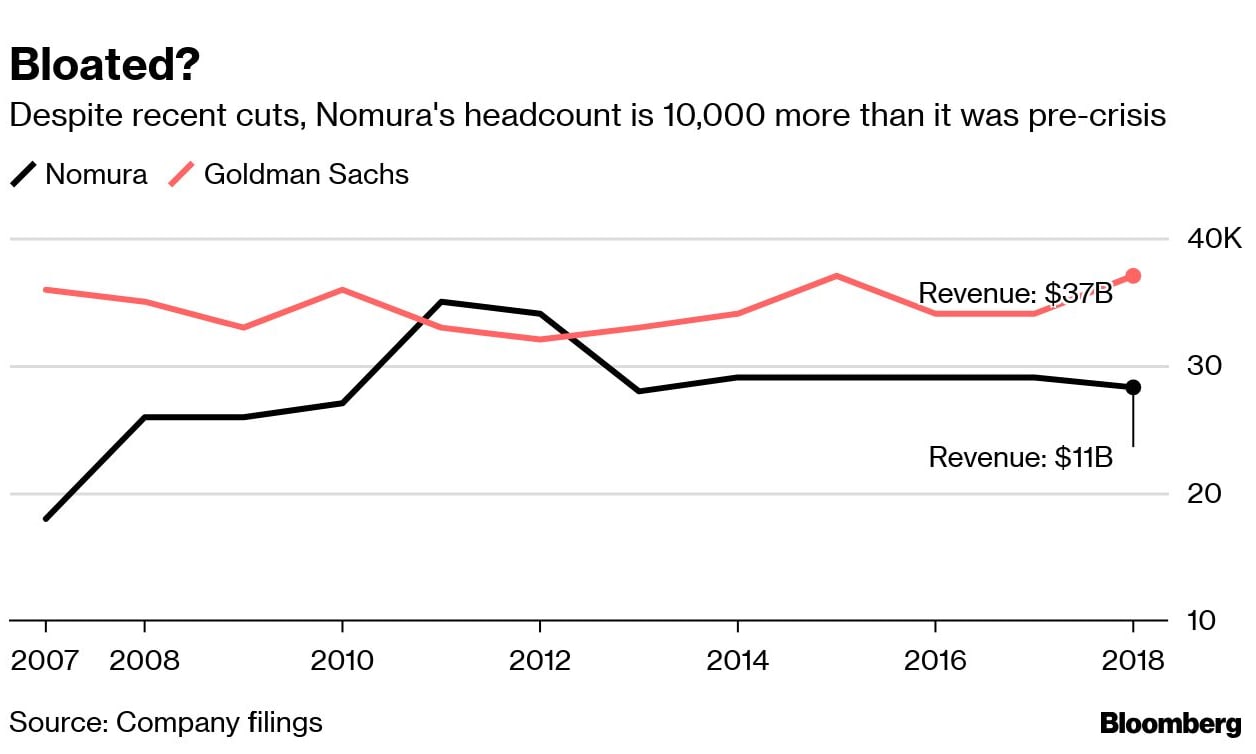

Despite failing to capture revenue from the Lehman business, Nomura’s headcount still reflects the bump caused by the arrival of 8,000 Lehman folks and more. The firm’s 2018 revenue was almost the same as it was in 2007, yet Nomura employs 10,000 more people now than it did then. In an interview last month, Nomura CEO Koji Nagai acknowledged the problem somewhat.

“The biggest reason is costs are too high,” Nagai said. “Revenue has risen modestly, but that was overwhelmed by costs.”

The bank has failed to make money in trading because it doesn’t allow highly paid traders to take risk, one of those recently let go said. Every increase in a trader’s risk position has to be approved by headquarters, the trader added.

“I was always aware that anything we decided to do in America was conveyed to Japan overnight,” says Max Chapman, who was head of the firm’s overseas business in the 1990s. “We would work all day and they would work all night translating what we were doing back to Tokyo so I would see people in the morning and they were kind of groggy.”

A New York-based banker for Sumitomo Mitsui echoes Chapman, saying that the American chief of the U.S. unit is often overruled by the Japanese co-head. Like other Japanese banks, Sumitomo Mitsui rotates the executives it sends to overseas units every three years, which also undermines the understanding and knowledge of those appointees of the regional market, the banker says.

“The rigidity of Japan’s rotation system has become a disadvantage,” says Jesper Koll, a Japan-based senior adviser at asset manager WisdomTree Investments Inc.

The domination of process over everything else is so overwhelming that a 10 cent error on a multi-million-dollar currency trade took several weeks to fix and involved dozens of people, recalls a former trader who used to work for a unit of MUFG in the U.S. All current and former employees asked not to be identified discussing internal matters.

An MUFG spokeswoman said such stories reflect the past at her company, which has been “advancing localization” with non-Japanese managers running the U.S. and European securities and investment banking units. “We are creating a structure where they can operate while exercising appropriate authority,” said Kana Nagamitsu.

Mizuho and Sumitomo Mitsui spokesmen declined to comment. A Nomura representative pointed to the company’s plans to improve overseas business through efforts such as increasing the use of digital technology for fixed-income trading.

Beyond Nomura and MUFG, Mizuho also sought to strike in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. In 2015, it hired about 130 bankers from Royal Bank of Scotland Plc in the U.S. Sumitomo Mitsui laid out ambitions to expand in global markets two years ago, saying it might add 250 positions abroad. While that has helped it climb the ranks in some products, such as investment grade bond underwriting in the U.S., Japanese banks still are absent from the top 20 in most other league tables. Mizuho and Sumitomo Mitsui’s total global markets revenue, including asset management, roughly equaled the trading revenue of RBS, which remains state-owned after the crisis-era bailout.

All of which highlights MUFG’s relative success via Morgan Stanley. The two companies merged their Japanese investment banking and trading units as well. They also have a cooperation deal on U.S. bridge loans, where Morgan Stanley uses the Japanese partner’s bigger balance sheet to lure advisory clients on mergers and acquisitions. A quarter of MUFG’s fiscal year 2018 profit came from Morgan Stanley dividends.

“They don’t have to run it, but they get the benefits,” said KBW’s Threadgold. “They also offer the vast global distribution network Morgan Stanley has to their corporate clients. It’s a win-win.”

--With assistance from Taiga Uranaka and Takashi Nakamichi.

To contact the authors of this story: Yalman Onaran in New York at yonaran@bloomberg.netViren Vaghela in London at vvaghela1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Hertling at jhertling@bloomberg.net

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.