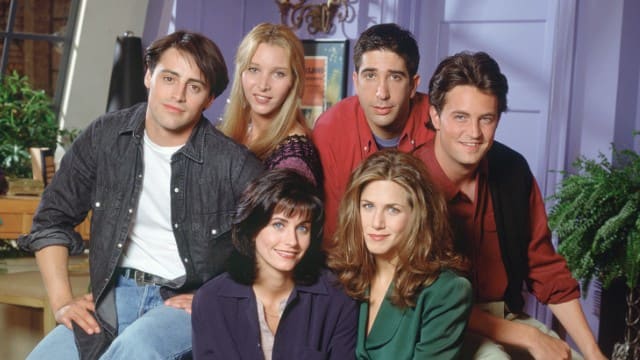

Last week, Jennifer Aniston, Courtney Cox, Lisa Kudrow, David Schwimmer, Matt Le Blanc and Matthew Perry took to their Instagram feeds to confirm the long-held suspicions of fans around the world: the "Friends" gang is getting back together for a reunion.

We don't know what form the show will take. But it puts a renewed and 21st century spotlight on the 1990s favorite -- which for many, defined a generation, and has for years after its run ended enjoyed enduring popularity in syndication and on Netflix. As even devoted fans can recognize now, "Friends" often ended up on the wrong side of cultural history, highlighting many troubling norms of its time. This reunion on HBO Max is a timely opportunity for fans and new observers to ponder exactly why many people still love this show, and to ask what the hopefully older, wiser group of "Friends" might potentially acknowledge on the Central Perk sofa, this time around. (Like CNN, HBO Max -- a streaming service set to launch in May -- is owned by Warner Media.)

For starters, the "Friends" reunion might take a stab at talking about the original show's glaring lack of diversity. While there were equivalent non-white sitcoms in the 1990s, it was a gigantic oversight for arguably the decade's biggest program -- set in one of the biggest, most diverse cities in the world -- to have such poor representation of anyone not straight, white, middle-class and thin.

David Schwimmer noted in a recent interview his awareness of the show's lack of diversity, suggesting there should be an "all-black 'Friends' or an all-Asian 'Friends'." Erika Alexander, a cast member of the show "Living Single," which also portrayed a group of young single city-dwelling friends and debuted a year before "Friends" took to Twitter to point out what appeared to be a glaring assumption that such a show hadn't already existed. Schwimmer replied in a tweet: "I didn't mean to imply Living Single hadn't existed or indeed hadn't come before Friends, which I knew it had."

Compared to shows like "The Fresh Prince of Bel Air," which handled not only racial politics, but issues like generational and class divides with humor and elegance, "Friends" remained pretty static in its cozy middle-class bubble. Any point of difference was used as a kooky reference -- "Phoebe used to be homeless, so she's super tough!" -- rather than an opportunity to explore a potentially juicy theme or raise viewers' social consciousness.

Issues which shouldn't have been issues -- like Monica's childhood fatness -- were used for cheap, offensive laughs. Plump, clumsy, naive adolescent Monica (shown through frequent flashback scenes over the years) wasn't even allowed to have the same personality as thin, efficient, sharp Monica -- she was just a "fun" extra character who sometimes just showed up.

On the rare occasions someone who didn't fit the mold appeared on "Friends," they were used as a foil for the main, L'Oreal-ready cast's experience. Take the treatment of Chandler's -- apparently, but not explicitly -- transgender dad, played by Kathleen Turner. Their identity wasn't ever addressed head-on in the show, but the general impression is that it's confusing, and therefore traumatic for Chandler. Their presentation is used as fodder for grim lines like, "Don't you have a little too much penis to be wearing a dress like that?" It'd be cool to see that relationship discussed. For instance, Turner has said that she wouldn't accept the same role now.

Of course, there are other LGBTQ concerns the gang could talk about. One of the show's longest-running jokes -- introduced within the first few minutes of the 1994 pilot -- is that Ross was dumped by his first wife, Carol, for another woman, Susan. While it was unusual in the 1990s to feature a gay female couple on TV, and particularly groundbreaking for its time to feature them as parents, that visibility is undermined by the main joke being that it's embarrassing for Ross to have been dumped for another woman. From Ross's first meeting with her, Carol's girlfriend Susan is painted as an unreasonable baddie, and the pattern of gay-is-a-punchline is set up for many seasons thereafter. The Susan of 2020 would deserve to be portrayed now as a total hero for putting up with it all.

"Friends" was hardly the only show of the era which failed to take gay female relationships seriously. When "Sex and the City"'s Samantha started dating a woman in the show's fourth season, her friends' responses are initially snide and disrespectful. Her friend Charlotte remarks: "Maybe she [Samantha] just ran out of men?" It's used as just another instance in which Samantha is judged for her sexual proclivity by her supposedly enlightened pals.

The slut-shaming mentality of the 1990s also occasionally emerged on "Friends." One of the early sticking points of Richard and Monica's relationship is how many sexual partners Monica has had. When Monica reveals the number, Richard -- a friend of Monica's dad and portrayed by Tom Selleck -- sits down, breathing a relieved sigh: "You had me thinking it was like, a fleet." The strong implication is that had the number been higher, that would have been a problem. It's a weird point to focus on, considering Richard dating Monica, whom he has known since she was a baby, is the equivalent of Joey, in 2020, dating Ross and Rachel's daughter Emma.

You have to hope that if dating comes up among the "Friends" of 2020, they might at least advocate for doing a few things differently in retrospect -- and indeed, all sexual interactions. Joey's womanizing, Ross's history as a controlling, jealous boyfriend, and Chandler's cruel treatment of his girlfriend Janice, are well-documented. But some early events outside the main cast are more sinister. In season one, when Rachel's boyfriend Paolo gropes Phoebe while she's giving him a professional massage, the gang treats the incident as a form of cheating. Phoebe even apologizes to Rachel for the fact that Paolo "made a move" on her. Post #MeToo, that "dramatic twist" reads very differently.

Considering how little the show commented on the part where touching women without consent is actual assault, it stands out even more today how hyper-sensitive the gang were to entirely benign events involving women's bodies or parenting. When Carol breastfeeds her son, Ben, early on in "Friends," Joey and Chandler make their horrified escape as soon as possible. This wasn't just a male thing on 1990s sitcoms, apparently; Carrie on "Sex And the City" legs it when she sees her friend Miranda feed her new baby. By contrast, actual problematic parenting -- see Ross hating on his son Ben's Barbie, and firing the male nanny for being "too sensitive" -- is seen as kind of cute. Less than two decades ago, men got credit just for being in the same room as their offspring.

So what might HBO Max's upcoming special have in store? You've gotta hope that by 2020, the gang has some perspective on the internalized -- and externalized -- misogyny of their show's youth. At the very least, they likely have a better understanding of the world beyond Central Perk, where objectifying women is bad, and ignoring stale gender binaries is good. Failing that, the best thing the "Friends" cast can do for themselves is probably ... make other friends.