(Bloomberg) --

The European Union has stepped back from the brink. Again.

Unprecedented in nature and ambitious in scope, the 2.4 trillion euros ($2.6 trillion) in total recovery spending unveiled by the EU -- anchored by 750 billion euros of joint debt issuance -- has already started to calm jittery markets and it might just restore a sense of unity to a bloc under severe strain.

With the economic pain spread unevenly across the continent, the initiative will mean a big step toward real fiscal union for the 27 member states and aims to recast the EU as a force for good rather than an irritating meddler.

Facing its worst recession in living memory, the EU has crossed a new bridge: It will harness its collective strength to raise massive amounts of money that won’t need to be repaid by the recipient countries.

Countries in the EU still value their sovereignty and so the bloc has always evolved by dipping toes in the water, often in times of crisis, rather than diving straight in. But with the creation of the euro and handing over control of policy areas like competition and trade, bit by bit, decade by decade, governments have exchanged their powers for the sake of common power.

Leaders will begin haggling over the details when they convene on June 19 -- perhaps even in person for the first time in months -- and the process will likely involve its fair share of bickering as all European projects do. But that won’t detract from the radical nature of what is now on the table.

“This is Europe’s moment,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told the European Parliament in Brussels on Wednesday. “We either all go it alone, leaving countries, regions and people behind, and accepting a union of haves and have-nots, or we walk that road together.”

Divided Continent

As the coronavirus death toll mounted in March, spreading northward from the overwhelmed care homes and hospitals of Italy and Spain, the EU had floundered, with member states set against each other in the scramble for resources to protect their own. In Italy, the opposition leader Matteo Salvini spoke openly of pulling his country out of the EU.

That, von der Leyen said at the time, was “a glimpse of the abyss.”

Wednesday’s proposals go some way to ensuring leaders don’t look back into it any time soon.The pandemic has ensured it’s happening again in a way that was unthinkable just three months ago when governments still couldn’t agree on the bloc’s long-term budget -- a far less drastic decision -- after two years of squabbling.

That it took Chancellor Angela Merkel, in the twilight of her career, to reverse years of German intransigence to call for bonds backed by the bloc’s central budget, reveals the seriousness of the matter. This isn’t just about helping out friendly fellow governments.

Nationalist groups are gaining footholds inside the EU borders, and on the outside it faces an increasingly assertive China and an antagonistic America, so this was about keeping the whole post-World War II European show on the road.

Franco-German Plan

The EU plan follows the general contours of a proposal presented earlier this month by Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron, and would see the commission, the bloc’s executive arm, issue 750 billion euros of debt with 500 billion to be disbursed as grants and the rest as loans. The latter may help appease budget hardliners who objected to joint debt issuance and presented an alternative blueprint made up entirely of loans.

But it’s far from a done deal.

Merkel herself said she expects negotiations and ratification of the plan to occupy much of the year and Sweden’s EU minister, Hans Dahlgren, told reporters his country won’t accept the plan as it stands. He was holding a video call with his counterparts from Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands on Wednesday afternoon to discuss their next move.

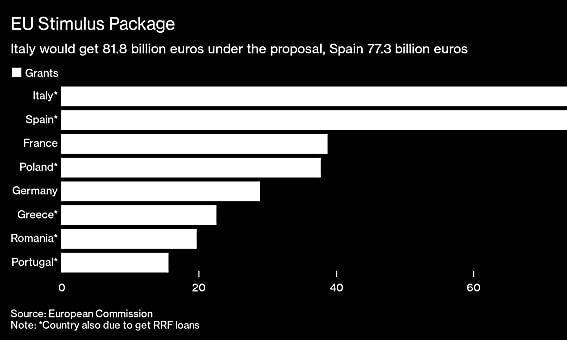

Under the commission proposal, Italy would get 81.8 billion euros in grants, Spain 77.3 billion euros, Greece 22.5 billion euros and France 39 billion euros, according to an official familiar with the details.

If endorsed, the plan will ease the pressure on the European Central Bank to act as the euro area’s main line of defense during a crisis. The central bank’s 750 billion-euro emergency bond-buying program has helped prevent borrowing costs from spiraling out of control and ECB policy makers are widely expected to expand the program as soon as next month.

But the program is testing the limits of what the institution is legally allowed to do. And the economic cost of the pandemic is still mounting.

“Mastering the economic recovery will require “an extraordinary effort to match this extraordinary challenge,” Merkel said in a speech in Berlin late Wednesday, citing her proposal with Macron and the European Commission’s plan.

Merkel, who said decisions on tackling the pandemic were among the “most difficult of my entire tenure” as chancellor, reiterated her mantra that Germany “will only prosper if Europe does as well.”

The significance of this week’s proposal lies not just in the amounts of money it would bring into play, but in the new form of fiscal solidarity it points to in the face of an existential threat, economists at Goldman Sachs said.

“The recovery fund sends an important political signal,” Goldman Sachs economists led by Sven Jari Stehn wrote in a note this week. “The Macron-Merkel proposal shows a deep commitment to Europe and raises the likelihood of further fiscal integration ahead.”

(Adds Merkel comment in 20th, 21st paragraphs.)

For more articles like this, please visit us at bloomberg.com

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.