New Delhi: In the winter of 1956, when the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai visited India, there was an unusual item on his itinerary: a visit to the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Kolkata. The visit derailed his schedule as Zhou kept on asking questions to the team of statisticians at ISI headed by its legendary founder, Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis.

At that time, ISI was at the centre of India’s efforts to build a cutting-edge statistical system and the National Sample Survey (NSS)—the first-of-its-kind household survey in the developing world—was run from there. It was at ISI’s NSS unit that Zhou “sat down on a table and refused to move until his questions had been satisfactorily answered”, according to the historian Arunabh Ghosh of Harvard University who authored a 2016 British Society for the History of Science research paper on Sino-Indian statistical exchanges.

“We want to learn from you…,” Zhou told Mahalanobis before he left. By the middle of the 20th century, India was a statistical powerhouse, setting standards for the rest of the world.

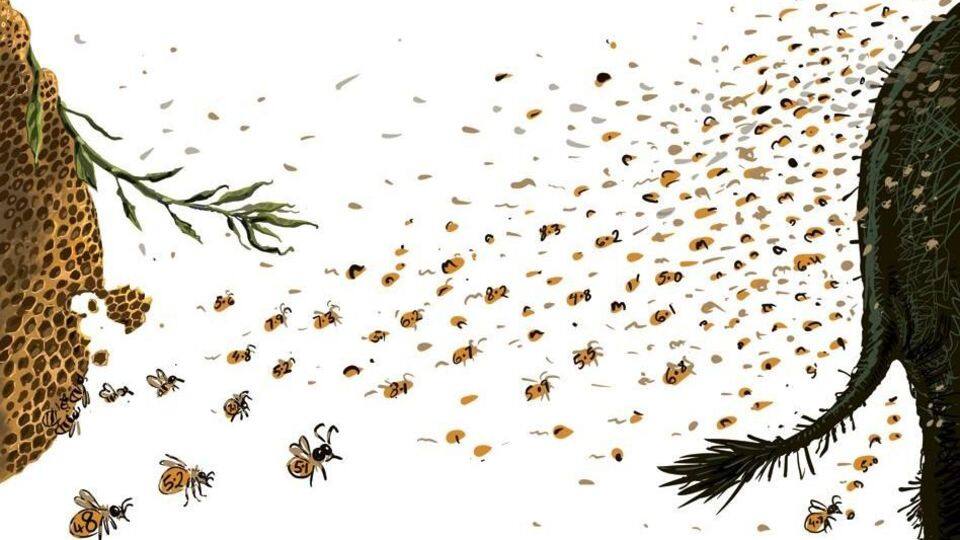

Since then, the quality of India’s official statistics and its reputation globally has suffered a steep decline. While this has been long in the making, never has India’s statistical crisis appeared as profound as it does today, with every other data release (or suppression) accompanied by controversy.

Even before the controversy over the new gross domestic product (GDP) series numbers could be resolved, a new controversy on an NSS consumption survey arose last year after the ministry of statistics and programme implementation (Mospi) decided to bury the report, citing “data quality” issues.

Today, unflattering comparisons are being drawn with China, where GDP figures have long been doubted, and where adverse reports are routinely suppressed. The credibility crisis seems to have now forced the mandarins at Mospi to revive a long-pending proposal to provide statutory backing and greater autonomy to the National Statistical Commission (NSC).

A statistical paradise

If NSC is really allowed to function as the apex authority on official statistics, it could shake up the statistical system. An empowered NSC would effectively mean that reports prepared under its watch can no longer be held back from the public, regardless of whether it flatters the government or paints it in poor light. It would mean that all statistical products, including the GDP series, would be independently audited. The strengths and weaknesses of the raw data used in these products would come out in the open.

In such a statistical paradise, analysts would no longer have to rely on sales of biscuits or of undergarments to gauge the health of the economy.

While the draft NSC Bill 2019 has raised hopes among some experts about the government’s intent to clean up the statistical mess, it has also raised concerns about whether the bill in its current form will allow NSC to achieve its goals.

The new bill proposes to set up a full- time NSC (it currently has a full-time chairperson and part-time members), a permanent secretariat, dedicated funds and powers to supervise core statistical products. It could address the functional needs of NSC. But some current and former NSC members fear that the bill does not provide the commission with the kind of authority and autonomy that it would need to restore the credibility of official statistics.

“I don’t think the bill gives the NSC the autonomy it was meant to have,” said a former NSC member on condition of anonymity. “The whole idea was that it should be an independent body accountable to Parliament and not to any minister or bureaucrat. Here (in the latest draft bill), the executive is part of the body.”

But not everyone is as dismissive of the bill.

The latest bill signals a desire to raise the credibility of official statistics, and is the first step towards that goal, said Sonalde Desai, a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland and director of the National Council of Applied Economic Research-National Data Innovation Centre.

V. Anantha Nageswaran, economist and a recent appointee to the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PMEAC), agreed, calling the bill a “first step in restoring the credibility of the Indian statistical system”.

The draft bill draws on the 2011 report of a committee headed by legal luminary N.R. Madhava Menon. The Menon committee had first recommended the setting up of an audit and assessment wing under NSC, to be headed by a “Chief Statistical Auditor”. The draft bill has a similar provision. It also retains the regulatory powers over core statistics that the Menon committee had envisaged.

A partial resurrection

However, there are some important differences between the current draft and the one presented by the Menon committee. To maintain the independent character of NSC, the Menon committee had said it was not in favour of appointing government officials as ex-officio members. The latest draft includes three ex-officio NSC members including the chief statistician of India, the chief economic adviser to the finance ministry (CEA) and the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

“Having ex officio members in the NSC is inconsistent with the objectives, namely, promoting public confidence, and achieving independence and integrity of official statistics, mentioned in the preamble of the draft Bill,” said M.V.S. Ranganadham, who was member-secretary to the Menon committee, and who retired as director general of the Central Statistical Office in 2018.

He added: “Secondly, if three ex officio members are included, there would be a danger of running the NSC with these three members without filling up the other vacancies. Thirdly, the three ex officio members are concurrently either producers or users of official statistics and hence, there will be a conflict of interest.”

The draft bill also suggests a shorter term (three years) compared to what the Menon panel recommended (five years); most experts believe that a five-year-term makes more sense for a body of this kind.

Unlike the Menon committee draft which envisaged NSC to be accountable to the government, to the public at large (through a dedicated website that would provide an account of NSC’s activities to the public) and to the courts (with a provision to sue NSC), the current draft bill does not lay down provisions enforcing public accountability. “It dilutes its accountability to the public,” said Nageswaran of PMEAC. “There has to be a dedicated NSC website in which minutes of meetings are published and NSC activities are listed.”

Overall, the current bill is a halfway house between where things stand today and where things should be, said P.C. Mohanan, a former NSC member, who resigned in protest against the suppression of an NSS jobs report in 2018. The bill does not give the kind of oversight powers that earlier panels such as the Rangarajan Commission had recommended but it addresses the functional needs of NSC, providing it with statutory backing and a secretariat, said Mohanan.

Pronab Sen, former chief statistician and former NSC chairman, thinks the bill in its current form could do more harm than good. “It is worse than the current model because at least in the current model, the NSC Chairman is a Minister-of-State, and in the government, these things matter,” he said. “When you have a body outside the government, he would essentially be treated as a PSU chairman and that would make a difference to how bureaucrats treat him.”

“To have autonomy and to insulate statistics from political pressures, I would prefer a CIC (chief information commissioner)-type model,” said Sen. “The CIC is embedded within the government but has the authority to take decisions without ministerial interventions.”

A question of authority

The question of authority comes up again and again in conversations with current and former members of India’s apex statistical body. And one reason for that is the undermining of NSC’s authority over time.

The idea of an independent apex statistical body was first mooted by a high-level committee chaired by former RBI governor C. Rangarajan. The decline in India’s statistical system was apparent to scholars and close observers by the turn of the century, and the Rangarajan Commission was asked to outline a plan to stem the tide.

“As official statistics play a major role in assessing the performance of government, it is important that such statistics are not only accurate, but are also trusted as such by the layman as well as by its principal users,” said the commission in its report. This objective could be met only if an independent “high-level policy-making body” oversees the statistical system.

Such a body will be institutionalizing the role that Mahalanobis had played as an independent and honorary statistical adviser to the cabinet, said the commission report.

In line with the recommendations of the commission, an NSC was set up through a government resolution in 2005, with the first panel tasked to formulate a law to provide statutory backing and teeth to the apex statistical body. A draft was indeed prepared but it never saw the light of day.

This was the first unsuccessful attempt at having a law-backing NSC; the Menon committee was the second such attempt. Instead of strengthening NSC, Mospi officials limited its remit over time, revealed a Mint investigation published last year.

Matters have only worsened since then, with NSC losing its long-held authority over even NSS surveys. “The authority now vests with the government,” said an NSC member on condition of anonymity. “They take the decisions and inform us, and in some cases, where they feel it is not an important policy decision, they don’t even do that unless asked. In case of the NSS consumption report, the decision to withhold the report was the government’s, not of the NSC.”

NSC now just gives recommendations that the government may accept or reject, said the NSC member. The draft bill may not mean much change in that respect other than making it mandatory for the government to explain in writing why it did not heed NSC’s advice, he added.

Reclaiming credibility

How successful the new NSC is going to be will therefore depend to a large extent on how much power the government or Mospi officials are willing to cede to it. But even if legal autonomy and authority are granted, NSC will still face a Herculean task in transforming the current statistical system into a nimble-footed force that can generate timely and credible data.

According to most experts, the current statistical system lacks the ability to process the large volumes of data that are being generated even within public agencies. Unlike in the Mahalanobis era, when statisticians at ISI imported the first digital computer in the continent to process NSS data (the ‘big data’ of that age), now our official statisticians are light years behind their peers elsewhere when it comes to dealing with large datasets.

Given that statistical officers are treated like other civil servants and transferred routinely, specialization has suffered, said former NSC member Mohanan. Coupled with the lack of incentives for research, this impedes innovation in the system, he added.

“Autonomy must be complemented with competence,” said Arvind Subramanian, former CEA, who has argued for “big-bang data reforms” in a recent research paper. “Then you get into a virtuous cycle and are able to carve out your own space, and anyone will think twice before undermining you. But it is easy to fall into a negative spiral as well: where you lose competence, stop being responsive to feedback from data users, and then lose your space to politicians and bureaucrats.”

Ultimately, data users should be able to trust the official numbers. Passing the “smell test” will determine the success of any statistical reform package.