In 1877, when Queen Victoria assumed the title “Empress of India”, at the special durbar was a 10-year-old prince. Mahboob Ali Khan was the nizam of Hyderabad and came to Delhi with his regent, the formidable Sir Salar Jung. It was the latter who wielded actual power, and while there were rumours that he meant to keep the boy forever under his thumb, the man was also a genuine champion of the state’s interests.

Indeed, when the viceroy pointed to Hyderabad’s “loyal allegiance” to the empire at the assembly, Salar Jung quietly translated it as “friendship” and “alliance” instead—to him, Hyderabad was not a vassal, it was “equal in sovereignty” to the British. But the viceroy would have none of it—he “corrected the intentional mistranslation” at once and made it clear to the little nizam that what he meant was unequivocal “obedience and fidelity”.

The nizams had come to Hyderabad as agents of the Mughals but quickly established their autonomy. Certainly, until 1857, they paid ceremonial homage to the badshah in Delhi, resisting British advice to declare themselves independent. Either way, by mid-19th century, it was the white man who became Hyderabad’s master, so that not only was the nizam saddled with a British army (to pay for which he was coerced to mortgage prized territory), but also debt on conditions that favoured English bankers. “Poor Nizzy pays for all,” mocked a newspaper, but successive rulers had no option but to accept such unfair terms. Resistance, when it occurred, was often through inventive non-military means. Once, for instance, when the queen sent Mahboob Ali Khan’s father a medal bearing her likeness, the nizam grabbed it before it could be pinned to his chest, and, placing it on his throne, took a seat on Her Majesty’s face.

But for all this, Hyderabad retained its importance, and though it came close to being annexed, in the end it survived imperial aggrandizement. Mahboob Ali Khan was 3 when he came to the gaddi, and such periods of minority rule in Indian states usually opened avenues for the British to widen their influence—they would appoint tutors to give lessons in loyalty to young princes and “improve” the administration in ways that dismantled old systems in favour of an anglicized bureaucracy. Salar Jung, however, prevented too many innovations—indeed, so resistant was he to British interference that as late as 1876, colonial agents lamented their lack of control—moral and academic—over the nizam. Instead, they reported that while Western education was imparted, Salar Jung had effectively turned the boy into a prisoner in his own palace, where “he is waited upon by 25 young women trained to debauch him”.

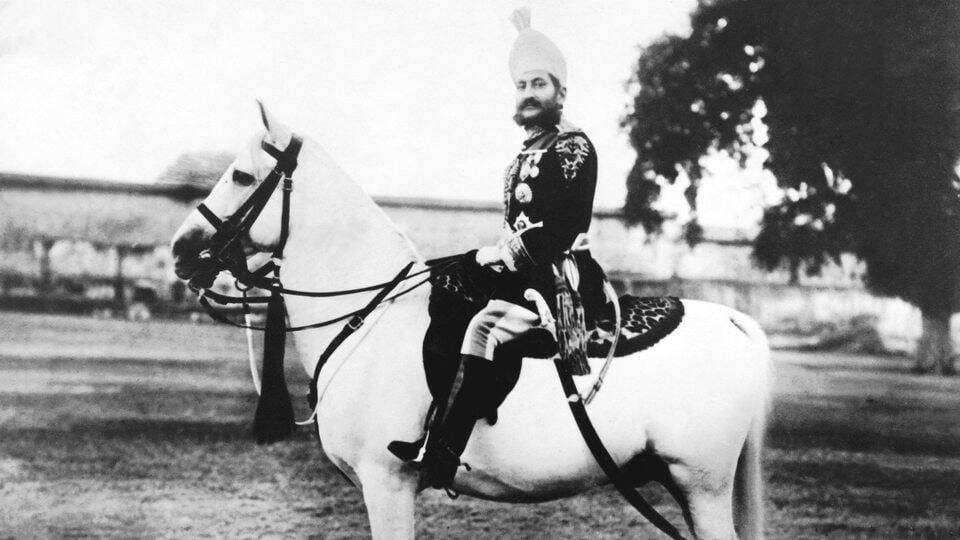

Whether or not this was an exaggeration, Salar Jung died in 1883 and the nizam came of age the next year and commenced his reign. His subjects were Telugu, Marathi, Kannada, and Urdu speakers, a large majority of them Hindu. The railways had already reached the state, as had electricity. The stage was set for great developments, and now there was also a young ruler whose generosity was proverbial.

One story, for instance, relates how a stranger wrote to the nizam asking ₹500 for his daughter’s wedding. When Mahboob Ali Khan sanctioned ₹5,000, his secretary wondered if he had made a mistake. Scribbling on the file, the nizam returned it, this time with the note: “15,000 is sanctioned.” His horrified aide learnt never to ask questions again of his imperious royal master.

While several public reforms received attention in Hyderabad, the culture at court continued in a state of ceremoniousness. It was not entirely surprising—with real power clipped by the British, court protocol offered a strange consolation. Arriving in Delhi once, the nizam discovered that he was expected to walk from his train to the exit to mount his elephant. Declining to do anything half as ordinary, he simply refused to leave the coach—instead he “had his meals…played cards” and generally whiled away precious time. Two days passed, and as other trains jammed behind him, pressure mounted on Lord Curzon (whose already poor opinion of Indian princes is not likely to have improved) to allow an elephant inside the station. Mounting the animal triumphantly now, Mahboob Ali Khan went to meet this very viceroy, before whom he almost mockingly swore allegiance to the British crown.

But this luxurious format of resistance could also quickly transform into a slippery slope to excess. Against advice, for instance, the nizam purchased what is called the Jacob Diamond—it was offered for twice the actual price, and he paid half in advance before deciding he didn’t want the item after all. The seller sued Mahboob Ali Khan, causing an irate nizam to throw the diamond into a sock and store it in a shoe. It was years before his heir rediscovered it, and this time it was put to better use—as a paperweight.

So, too, the nizam never repeated his clothes, with the result that not only did he end up with a wardrobe 77m long, but rumours circulated that his valet was selling him back his own old clothes, earning an illicit profit. On another occasion, Mahboob Ali Khan so liked a fabric that he had five years’ supply purchased in advance so that nobody else might wear the same material—to him, the world consisted of things he liked, and things he didn’t.

In 1911, however, this life of extravagance wound to a close. The nizam was surrounded by intrigue, with one wife reportedly placing pressure on him to declare her son heir to the throne. Storming out of the palace, Mahboob Ali Khan decided to binge on alcohol for three whole days, till he was comatose. And that is how, in his mid-40s, the man who was once described as “not wanting in ability” should he choose “to apply himself to public business” went to the grave—a legend where princely splendour was concerned but a tale of tragedy if his full productive potential was the measure.

Medium Rare is a column on society, politics and history. Manu S. Pillai is the author of The Ivory Throne (2015) and Rebel Sultans (2018).

He tweets at @UnamPillai